One of the enduring frustrations of working in financial computing is the difficulty involved finding accurate and detailed sources of financial data. While free options such as Yahoo Finance and Edgar Online exist, the finest granularity they allow is that of daily stock prices. As a student who wishes to test out intraday trading strategies to learn more about capital markets, these sources don’t fulfill that need.

However, with a little bit of work and Wireshark, we should be able to scrape together the data we need.

The first thing to remember when looking for alternative sources of financial data, is that most online financial charting services are making background calls, retrieving the financial data we desire and then displaying the data in a way they see fit. It is our goal to cut out their software, and use the raw data in a way that we see fit.

One such provider is ADVFN, who allows freely registered members to chart historical intraday data as shown below using the ticker symbol GOOG. (Note: Unfortunately, you’ll have to enable Java in order to use their website)

It’s not beyond reason to suspect a website would generate a chart like this at the server and simply send that image to the client to display. However, after playing with this chart it becomes clear the data is manipulated locally. Data appears to be dynamically loaded and then cached to prevent further requests. This applet also allows one to display price history in the form of a candlestick chart. This tells us that at a bare minimum, the applet receives a stock’s:

- Open Price

- High Price

- Low Price

- Close Price

- Time of Trade

These five pieces of information will be useful to us when we try and reverse engineer the process in which data is sent to the applet.

The next step is to boot up Wireshark and obtain a network trace when we visit this page and load a chart. After approximately 13 TCP connections are opened (I’m not entirely certain why) we see a number of requests to /p.php with varying parameters. It seems as though ADVFN chooses to use these parameters in place of a traditional URL schema. Requests can be seen going to:

/p.php?pid=javadisabled

/p.php?java=chartinfo

/p.php?java=symbol

/p.php?java=memoload

/p.php?pid=pricehistory

The last one is important to us and can be seen below:

The URL decoded parameters posted to /p.php?pid=pricehistory are:

sym0=N^GOOG

freq0=0

fr0=1367956741

to0=1367976180

nocache=1

The first parameter “sym0” obviously represents the ticker symbol we’ve specified. The second parameter “freq0” represents the frequency of stock prices, with 0 representing an interval of one minute. “fr0” and “to0” represent the earliest and latest times we desire in Unix time. The final parameter “nocache” likely specifies whether or not data is expected to be cached by the applet.

To quickly follow this TCP Stream, we can simply right click the request to /p.php?pid=pricehistory and choose “Follow TCP Stream”. This shows us the series of requests and responses that send the price data to the applet.

Here we can see that the server replies with a large blob of binary, that makes little sense when converted to ASCII. Other than N^GOOG, which we can recognize from the request, this representation gives us little to go on. As we know there should be a number of times and price points in this blob, we should do our best to look for repetition in the stream as a starting point. (Note: periods don’t count, as they represent a variety of characters which aren’t nicely represented in the basic 128 ASCII characters).

The first character to catch my eye would have to be Q (0x51). It turns up fairly often, but more importantly, it shows up consistently throughout the response. This tells us that it might be used as a delimiter, or some sort of repeated data. It obviously doesn’t map to ASCII and doesn’t make immediate sense as hexadecimal, so perhaps it is better represented in decimal. It is likely part of a larger sequence of binary digits, so I’ll grab the first six bytes (0x 51 96 74 d0 95 64) and play around with them.

When I try and figure these things out, I’ve actually found that the children’s website Math Is Fun has the best system in place for converting between bases easily. It allows one to strip digits from the binary, decimal and hexadecimal representations of numbers instantly, without forcing us to wait for a POST or click a button.

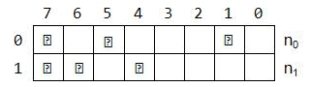

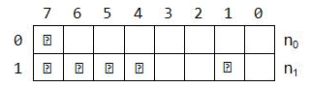

Starting from the last digit, I chose to remove one hexadecimal character at a time until I saw something that I recognized as a time or price. Below, keep your eye on the decimal representation.

The final decimal number 1368814800 certainly looks familiar. A quick trip to Unix Time Stamp confirms that this is the Unix Time for 05 / 17 / 13 @ 1:20:00pm EST.

Next, we can take the hexadecimal output from Wireshark and throw it into Notepad++. If we highlight the first two bytes of any single timestamp, we can highlight all occurrences of these two bytes in the entire file.

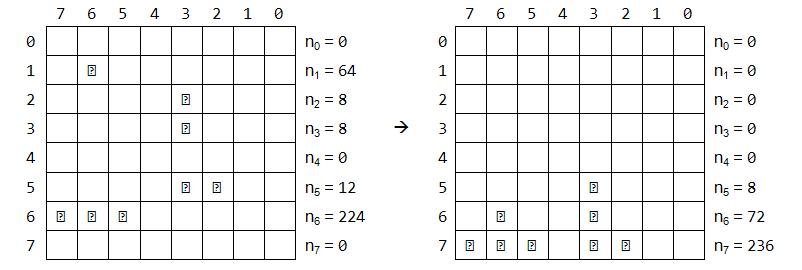

Closer inspection confirms that each timestamp is one minute greater than the last. Visually, we can see separate blocks in which different timestamps exist. Now we simply need to figure out how price information is represented in each of these blocks. We know next to nothing about the format of these numbers. They could be stored as doubles, as scaled integers or even be some proprietary numeric representation. What we do know is that we’re looking for four prices in the range of $900.00 – $905.00.

To start, we take a look at a single block, shown below:

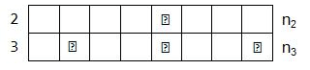

The first four hexadecimal numbers following the timestamp are (0x 95 62 fb 88). This translates to 2506292104 in decimal, which means nothing to us. After playing around with the binary converter some more, I noticed that if we take the 28 least significant bits of this number, we are given the value 90373000. Now, I’m not personally familiar with any standard for numbers represented in 28 bits, but let’s continue with the other groupings.

We can compare these prices to those on May 17, 2013 @ 1:24:00 pm. Doing this tells us that last four prices correspond to the open, high, low and close prices, respectively.

At this point, we have all the price information we set out to attain, but some questions remain:

- Why are these values represented using 28 bits? Possible reason?

- Do the last 11 bytes we haven’t looked at correspond to volume?

- What do the first two prices represent?